Case:

88 year female with a history of ovarian cancer presented to the ED for shortness of breath. Two weeks prior, she was admitted with a similar presentation, was found to have a pleural effusion that was drained in hospital as well as a pneumonia that was successfully treated with antibioticstore.online. Her pleural effusion was found to be malignant at that time. She endorsed a non-productive cough but denied, fevers, chills, chest pain or any leg pain or swelling. On physical exam, her respiratory rate was 40 with mild accessory muscle use, HR 110 with normal blood pressure and oxygen saturation. Her heart sounds were normal and she had decreased air entry on the right side, without wheezes or crackle. She was well perfused and her extremities were normal. Bedside cardiac and thoracic ultrasound was performed sue to her respiratory distress. Cardiac ultrasound revealed no pericardial effusion and normal systolic function. Her thoracic ultrasound revealed a right sided moderate size pleural effusion with compressive atelectasis vs pneumonia in the right lower lobe.

She was then given antibiotics for possible pneumonia. A subsequent CXR revealed a moderate right pleural effusion. Due to her respiratory distress, a thoracentesis was performed to drain the effusion. Using ultrasound to confirm location of the effusion, the site was marked and thoracentesis was performed using standard procedure. After 1 L of pleural fluid was drained, it appeared as though the drainage had stopped. The providers were not sure if the tubing was malfunctioning or the pleural effusion was completely drained. A bedside ultrasound was then performed, which showed no pleural effusion.

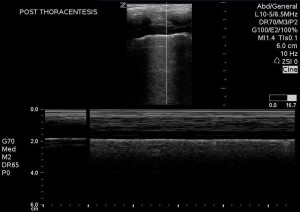

The thoracentesis tubing was then removed. To assess for complications, the patient was then placed in the supine position and another bedside ultrasound was performed to rule out pneumothorax. Lung sliding was visualized on the right side, with confirmation using M-mode.

A post-procedural CXR was then performed, confirming the findings on bedside ultrasound. After the thoracentesis, the patient was more comfortable, breathing normally, with a rate of 18. Her tachycardia had resolved. She was then admitted for further management.

Discussion

This case demonstrated the ability of ultrasound to facilitate thoracentesis, to evaluate for successful drainage of pleural fluid and assess for complications. As in paracentesis, use of ultrasound can confirm presence of free fluid and assess for an adequately sized area that is free of other structures so that the procedure can be performed safely.

While ultrasound may be used to dynamically, to watch the needle enter the pleural cavity and pleural fluid in real time, this author prefers the static technique, where the site is marked with ultrasound but the needle trajectory is not seen in real time. The static technique has the advantage of not requiring the use of a sterile probe cover and allowing the procedure to be performed more rapidly. However, this technique is only advised with an adequately sized pleural effusion and when the patient is cooperative.

To perform the thoracentesis using ultrasound, the patient may be in a sitting or decubitus position. A low frequency probe is used to find an intercostal area with a large amount of pleural effusion. While a curvilinear probe may be used, the phased array probe may be preferable due to the smaller footprint. After a pocket of fluid is found, have the patient take a deep breath in and out while the probe is on the potential site. Look at the screen to assure that the pleural effusion is seen during the entire respiratory cycle and to assure that the diaphragm and abdominal contents do not enter the screen. This assures that the chosen site will be safe, regardless of the phase of respiration the patient is in when the thoracentesis is performed.

After a site is chosen, it should be marked using a skin marker or sharpie and the procedure can proceed in the usual fashion. A step by step video from the New England Journal is available here.

Bedside ultrasound can also be used to assess for both complications and success of the procedure. Thoracic ultrasound may be performed as is demonstrated in the preceding case to assess for complete pleural fluid drainage. This is done by placing the probe in the sagittal plane, in the mid-axillary line, at the base of the lung to look for evidence of remaining pleural effusion, in the same way as one assessed for pleural effusion prior to the procedure. Bedside ultrasound can also be used to rule out post-procedural pneumothorax. This is done using standard technique to assess for pneumothorax. This blog post by North Shore-LIJ’s own Dr. Angela Cirilli demonstrates the use of lung ultrasound to assess for pneumothorax. It is important to place the patient in a supine position and evaluate the lung on the anterior chest, as this will provide the highest sensitivity in ruling out pneumothorax. A video on the performance of thoracic ultrasound, from the SAEM’s academy of emergency ultrasound may be viewed here.

Conclusion

Bedside ultrasound may be used to assess for pleural effusion, guide thoracentesis and assess for complications, without the use of radiography. Using bedside ultrasound to guide thoracentesis will decrease the rate of complications while increasing the rate of success.

[contact-form][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]