Case

An 87 year old female with a past medical history of untreated metastatic thyroid cancer presented with two weeks of gradually worsening anasarca, dyspnea, orthopnea and fatigue. Her ability to complete her activities of daily living had significantly decreased over this time. Her physical exam was significant for bilateral lung crackles, diminished heart sounds, and pitting edema to the abdominal level. An EKG was obtained that showed diffuse low voltages and T wave inversions in leads II, III, aVF, V2, V4, V5, and V6. Due to the diminished heart sounds and low voltage on EKG, a bedside cardiac ultrasound was performed and the following image was obtained, showing a 2.5 centimeter circumferential pericardial effusion:

The cardiac ultrasound was also significant compression and underfilling of the right ventricle in systole—signs suggestive of cardiac tamponade. The patient was admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit for monitoring and taken for pericardial drainage by Interventional Radiology 36 hours later; 1L of fluid was drained from the pericardium with an additional 35cc draining daily for the next 2 days. The patient’s symptoms and physical status improved and she was then discharged home several days later to follow up with her primary care physician and cardiologist.

Discussion

Bedside ultrasonography for evaluation of cardiac tamponade is an essential skill for the emergency medicine physician. Determining whether tamponade is present can dramatically change management and the rapidity with which intervention has to be performed. A recent review on bedside ultrasound for diagnosis of pericardial effusion and tamponade cited a study that compared emergency medicine physician who underwent a 16 hour training course on emergency ultrasonography, including 1 hour of instruction dedicated to echocardiography and 4 hours of dedicated echocardiography practical training, to cardiologists performing the same echocardiography studies. Results showed that, using cardiologist performance and interpretation as the gold standard, emergency physicians were able to detect pericardial effusion and tamponade with a sensitivity of 96%, specificity of 98%, and overall accuracy of 97.5%. These results would suggest that the basic ability to determine presence or absence of pericardial effusion and its effect on cardiac function is a reasonable and attainable skill for the emergency physician to allow for rapid assessment and diagnosis of pericardial tamponade so the patient can be definitively managed; whether by emergent pericardiocentesis, monitoring with later drainage, or transfer to a facility with the resources to manage this type of cardiac emergency.

Once a pericardial effusion has been identified, the critical issue becomes determining whether signs of cardiac tamponade are present. Cardiac tamponade occurs when the pericardial pressure exceed the right ventricular end diastolic pressure (RVEDP). Clinically, this presents as hemodynamic compromise in the setting of a known pericardial effusion. Signs and symptoms may include shortness of breath, hypotension, tachycardia, or chest pain. EKG may show low voltages, or signs of pulsus paradoxus. Chest X-Ray may demonstrate an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Importantly, signs of cardiac tamponade can be seen very early, sometimes prior to clinical instability. Ultrasonographic signs of cardiac tamponade may include: right atrial collapse (50-100% sensitive, 33-100% specific), right ventricular collapse (48-100% sensitive, 72-100% specific), left atrial collapse (13% sensitive, 98% specific), and mitral inflow respiratory variability. Pulsus paradoxus refers to an abnormally large drop in systolic blood pressure with inspiration (>10 mm Hg). Pulsus paradoxus occurs because inspiration increases venous return to the right side of the heart, but results in decrease left sided filling. The opposite occurs with expiration (left sided filling increases and right sided filling decreases). With increased pressure on the heart from a pericardial effusion, this difference is exaggerated and can be evaluated sonographically by assessing flow across the tricuspid and mitral valves in inspiration and expiration.

Fig. 1 Physiologic effects of cardiac tamponade resulting in increased inter-ventricular dependence (pulsus paradoxus)

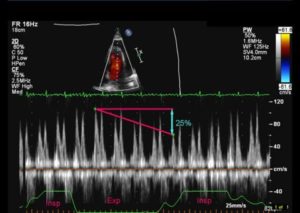

To assess for mitral/tricuspid respiratory variation, pulse wave Doppler analysis of the tricuspid and mitral valve flow velocities is assessed. With normal cardiac function, inspiratory increase in Doppler velocities at the tricuspid valve and decreased velocity across the mitral valve should be less than 20% compared to the velocity in expiratory phase. In cardiac tamponade, the difference in velocity between inspiratory and expiratory phases may be exaggerated to up to 40%. Variability of greater than 25% is suggestive of tamponade. An example of such a measurement of velocity difference in inspiratory vs expiratory phase is seen below:

The follow up echocardiogram performed by cardiology showed normal mitral respiratory variability but significant tricuspid variability, indicating the need to check both during a tamponade assessment.

Conclusion

Training in basic cardiac ultrasound evaluation is an essential tool for the Emergency Medicine physician in order to identify pericardial effusion and potential tamponade in a rapid manner. Though cardiac ultrasound can be daunting and complex, the basic principles and techniques are attainable by the average emergency physician, including ventricular or atrial collapse and mitral/tricuspid respiratory variation. Such identification and evaluation can assist the physician in early diagnosis of these conditions which can inform early management and interventions to improve patient outcomes and reduce mortality.

References

1Ceriani, Elisa, MD, and Chiara Cogliati, MD. “Update on Bedside Ultrasound Diagnosis of Pericardial Effsuion.” Internal Emergency Medicine (2016): n. pag. Web.

2Fields, J. Matthew, MD, and Pablo Aguilera, MD. “Cardiac Ultrasound in Patients with Chest Pain.” Current Emergency and Hospital Medicine Reports (2015): n. pag. Web.

3Goodman, Adam, MD, Phillips Perera, MD, Thomas Mailhot, MD, and Diku Mandavia, MD. “The Role of Bedside Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Tamponade.” Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock 5.1 (2012): 72-75. Web.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”1_4″][et_pb_team_member admin_label=”Person” name=”Dr. Josh Guttman, MD, FRCPC” position=”Reviewer and Ultrasound Editor – theEMPulse.org ” image_url=”http://theempulse.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Guttman-e1453253661766.jpg” animation=”off” background_layout=”light” twitter_url=”https://twitter.com/josh_guttman” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” saved_tabs=”all”]

Dr. Guttman graduated from the at Mt. Sinai Medical Center Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship and is now an Attending Physician at the LIJ Division of Emergency Ultrasound.

[/et_pb_team_member][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]