HTP?! 1 in a… ok, not near a million, but still.

The Bleeding Pregnant Patient

P. Schmalbach, MD, PhD, E. Mizrachi, MH Raj, J. Reisner

D. Dexeus, M. Richman

Case

A 25-year-old female G6P3A2 with LMP 6 weeks before arrival initially presented to the Emergency Department (ED) complaining of heavy vaginal bleeding, abdominal cramping, and a positive home pregnancy test. Her abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding began 2 days before arrival. At time of arrival the bleeding was associated with clots and she reported 1 pad per hour. Her abdominal pain was crampy, suprapubic, intermittent, and non-radiating. She had no pertinent past medical or surgical history. Her vital signs were stable and within normal limits. Physical examination was notable for a non-tender abdomen, closed cervix without cervical motion tenderness, minimal spotting in vaginal canal, and left-sided adnexal tenderness.

What would you do?

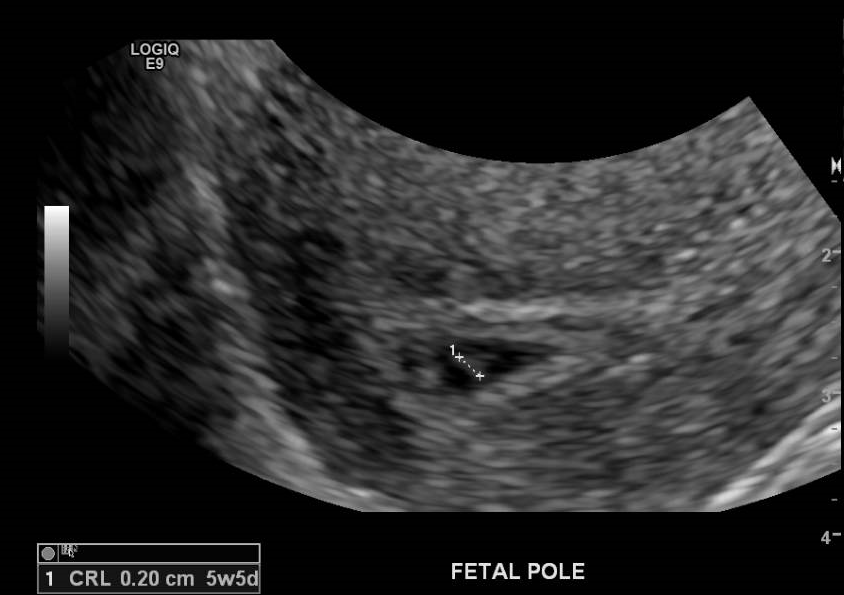

The pt. received labs and an official ultrasound was ordered. Blood work was remarkable for Hg of 11.9 with beta-HCG of 5,736. Radiology-performed TVUS showed an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) characterized by a gestational sac, yolk sac, fetal pole, and probable fetal cardiac activity that was too small to quantify (Images 1-4). There was trace complex fluid in the left adnexa. The impression was of an IUP at 5 weeks and 5 days and a possible exophytic L hemorrhagic ovarian cyst.

The patient was hemodynamically stable with bleeding that had diminished during her ED stay, and she had no clinical signs of anemia. She was discharged with follow-up for serial HCGs and elective termination for her unplanned and undesired pregnancy. She was given strict return precautions for worsening abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding, as well as signs/symptoms of anemia. She was amenable to the plan and discharged home.

The next day she returned to the ED complaining of worsening suprapubic pain and bleeding, as well as lightheadedness. Overnight, her bleeding increased from 1 pad per hour to 3 pads per hour. Her vital signs remained normal, but her physical exam was now significant for the presence of suprapubic pain in addition to left adnexal tenderness.

An ED-performed transabdominal point-of care-ultrasound showed an IUP and left-sided heterogeneous mass without intraperitoneal free fluid. This prompted a Radiology-performed TVUS to better define the adnexal lesion. The structure in the left adnexa which had been thought to be a hemorrhagic cyst and less likely heterotopic pregnancy was now more complex. There was an increased amount of fluid vs. hemorrhage tracking inferiorly in the cul-de-sac of Douglas. She went to the operating room for a diagnostic laparotomy. A salpingectomy was performed; pathology confirmed the suspicion of a tubal heterotopic pregnancy. She was discharged from the hospital 3 days later and had no complications.

Discussion

Heterotopic pregnancy in the setting of spontaneous conception is rare. The incidence has been estimated at 1 in 8,000- 1 in 30,000 pregnancies.[i] In patients using assisted reproductive technologies, the rate of heterotopic pregnancy is higher (0.2%-1%).[ii] Risk factors are similar to risk factors for ectopic pregnancy and include anything that disrupts the normal passage of the embryo into the uterine cavity.[iii] These include prior ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, tubo-ovarian abscess, smoking, and increasing number of lifetime sexual partners.

There is an increase in the number of Emergency Physicians performing bedside ultrasonography to differentiate lower abdominal pain in fertile females. A study by Stein et al.[iv] showed that Emergency Physician-performed ultrasound looking for ectopic pregnancy had an excellent sensitivity (97-100%) and negative predictive value (near 100%). However, the diagnosis of a heterotopic pregnancy is often more difficult than diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy. The presence of an IUP may falsely reassure the provider, and ruptured corpus luteal cysts in pregnancy in pregnancy are much more common (1 in 384, per a review of 26,909 pregnancies)[v] than heterotopic pregnancies. A heterotopic pregnancy may appear as a gestational sac with a yolk sac or even as an early conceptus with a heartbeat. In these cases, it is easy to identify the heterotopic pregnancy. However, if it appears as an anembryonic gestational sac or as a heterogeneous mass in the adnexa, it may be difficult to differentiate from a simple ovarian cyst or hemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst.

Take homes

Pts. with risk factors for ectopic or heterotopic pregnancy require increased investigation and follow up. [vi.]

50% of patients with ectopic pregnancy will have no risk factors[vii]

The beta-HCG is a poor predictor of heterotopic pregnancy because often it will be within a range consistent with normal pregnancy.[viii]

In conclusion, heterotopic pregnancies are rare, especially in the setting of pregnancy by spontaneous conception. The astute clinician must be suspicious of heterotopic pregnancy when a patient has first trimester pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding with risk factors for ectopic pregnancy or abnormal imaging. Strict return precautions are critical in a patient without a clear diagnosis of heterotopic pregnancy, but who is hemodynamically stable and reliable.

References

[i] Hassani KIM, Bouazzaoui AE, Khatouf M, et. al. Heterotopic pregnancy: A diagnosis we should suspect more often. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3(3):304. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.66563.

[ii] Ji Sun Lee,1 Hyun-Hwa Cha,1 Ae Ra Han, et. al. Heterotopic pregnancy after a single embryo transfer. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016; 59(4):316–8. Published online 2016 Jul 13. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2016.59.4.316.

[iii] Marion LL, Meeks GR. Ectopic Pregnancy: History, Incidence, Epidemiology, and Risk Factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(2):376-86. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182516d7b.

[iv] Stein JC, Wang R, Adler N, et al. Emergency Physician Ultrasonography for Evaluating Patients at Risk for Ectopic Pregnancy: A Meta-Analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):674-83. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.563.

[v] Raziel A, Ron-El R, Pansky M, et. al. Current management of ruptured corpus luteum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1993;50(1):77-81.

[vi] Panelli DM, Phillips CH, Brady PC. Incidence, diagnosis and management of tubal and nontubal ectopic pregnancies: a review. Fertil Res Pract. 2015;1:15. doi:10.1186/s40738-015-0008-z.

[vii] Barnhart KT. Clinical practice. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(4):379-87. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0810384.

[viii] Wang PH, Chao HT, Tseng JY, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for heterotopic pregnancies: a case report and a brief review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;80(2):267-71.