Case:

A 58 year old male with no significant past medical history presented to the ED complaining of pain to the back of the left ankle for 2 weeks. He is on no medications and is a non-smoker. His injury occurred when playing handball 2 weeks earlier, where he felt a sudden pain to his left ankle while he was running. He thought he had only sustained an ankle sprain and therefore did not seek medical attention. However, his symptoms persisted for 2 weeks, so decided to have his ankle evaluated. He had been able to bear weight, was walking with a limp and had not taken any medication for the pain and swelling. He denied any systemic symptoms, any other injuries or any previous injuries to that extremity.

On physical exam, he had normal vital signs and was in no apparent distress. Exam of his left lower extremity revealed edema and ecchymosis to the posterior portion of his foot ankle, as well as tenderness along the Achilles tendon. Thomson test revealed no foot plantarflexion upon squeezing his calf on the affected side.

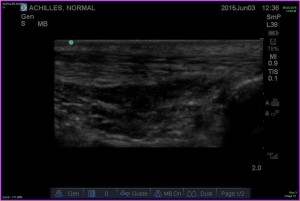

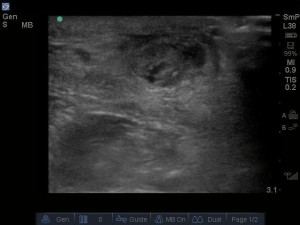

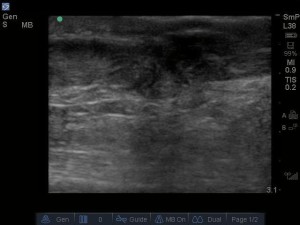

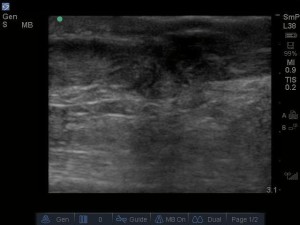

To confirm the diagnosis of complete Achilles tendon tear, a bedside ultrasound of the Achilles tendon was performed. Images of both the affected and unaffected achilles tendons are included in the images. The ultrasound revealed 2 separate tendon fragments separated by an anechoic space, confirming the diagnosis. Orthopedics was consulted and the patient was placed in a splint in the equines position with close follow up for surgical planning.

Discussion:

Achilles tendon injuries are common presentations to the ED. Differentiating achilles tendon tears from tendinosis is important in the ED, as partial or complete ruptures need to be immobilized, while complete ruptures often need more urgent operative repair. While physical exam, including a defect in the achilles tendon and a positive thomson test may be sufficient to make the diagnosis, physical exam may be limited in the acute setting due to edema and may not be diagnostic.

When the diagnosis remains unclear after a history and physical exam, imaging is often pursed. Imaging options include ultrasound and MRI. While MRI is considered the best imaging modality, the high cost and limited availability in many centers may be a limiting factor. Ultrasound is advantageous due to decreased cost, better availability and the ability to perform dynamic imaging of the Achilles tendon.

There is very poor evidence on the diagnostic imaging of achilles tendon ruptures. The best of studies comparing imaging to surgical findings show a sensitivity and specificity of MRI being 91% and 50% respectively, while ultrasound has a sensitivity and specificity of 96-100% and 83-100% respectively. Due to lack of evidence, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons guidelines on achilles tendon rupture could not recommend for or against routine imaging.

Bedside ultrasound can be used to evaluate for achilles tendon rupture. While it has not been formally studied, a tendon rupture seen on bedside ultrasound can assist the emergency physician in proper diagnosis and timing of orthopedic referral.

To perform the exam, place the patient in a prone position. A high frequency linear probe should be placed longitudinal plane over the achilles tendon at the level of the calcaneus. The probe marker should be directed proximally, per usual ultrasound convention.The achilles tendon appears as a fibrillar structure, with linear striations densely packed together. It appears superficially, just below the skin and soft tissue. The achilles should be followed proximally until it ends at the gastrocnemius muscles. The probe can then be rotated into transverse plane and the achilles can be followed distally until it’s calcaneal insertion.

Normal achilles tendon will have a homogenous architecture throughout the tendon, with the fibrillar striations clearly identifiable. An achilles tendon rupture is diagnosed when a hypoechoic or anechoic density is seen interrupting the normal tendon architecture. When the tear is complete, the proximal and distal ends of the tendon can be identified, retracted away from the site of the tear. In a partial rupture, part of the tendon remains intact, and no tendon retraction is seen. Evidence of tendon heterogeneity may also be seen in transverse as confirmation, however, this is less useful than the longitudinal view. To assist in confirmation of partial vs complete rupture, the tendon should be assessed dynamically throughout its range of motion by dorsiflexing and plantarflexing the foot. In a complete rupture, the proximal achilles tendon will have no movement, while in a partial rupture you will see some movement of the proximal achilles tendon

As in all musculoskeletal ultrasound, the sonographer should be aware of anisotropy, so as not to falsely diagnose a tear when it is not present. Anisotropy is the concept whereby if the structure of interest is insonated at a specific angle, the returning echos do not reach the probe and the structure appears anechoic, despite it being normal. Therefore, if there appears to be a tear in the achilles, the sonographer should adjust the angle of insonation, assuring that the tendon appears torn at multiple angles. By doing this, the sonographer can assure his or herself that the abnormality seen is not a false positive due to anisotropy.

In conclusion, use of bedside ultrasound may assist in confirming the proper diagnosis of an achilles tendon rupture and may assist the clinician in appropriate treatment and follow-up.

References:

Adikhari S, Marx J, Crum T. Point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis of acute Achilles tendon rupture in the ED. AM J Emerg Med. 2012;634. e3–634.e4.

Calleja M1, Connell DA. The Achilles tendon. .Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010 Sep;14(3):307-22. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254520. Epub 2010 Jun 10.

Margetić P, Miklić D, Rakić-Ersek V, et al.Comparison of ultrasonographic and intraoperative findings in Achilles tendon rupture. Coll Antropol. 2007 Mar;31(1):279-84.

Lehtinen A, Peltokallio P, Taavitsainen M. Sonography of Achilles tendon correlated to operative findings.

Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1994;83(4):322-7.

Hartgerink P, Fessell DP, Jacobson JA, van Holsbeeck MT. Full- versus partial-thickness Achilles tendon tears: sonographic accuracy and characterization in 26 cases with surgical correlation. Radiology 2001; 220: 406–412.

Lee KS. Musculoskeletal sonography of the tendon. J Ultrasound Med [contact-form][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form] 2012 Dec;31(12):1879-84.

Chiodo CP, Glazebrook M, Bluman EM, Diagnosis and treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010 Aug;18(8):503-10.,